You're overspending because you lack values

Overconsumption is a spiritual problem, not a money problem. Lessons about desire from "Spirited Away".

One morning in January, I woke up and it was like a spell had been broken the way I looked around my room and saw how dull everything was, not because it was lacking but because of how full it was of stuff.

Stuff I didn’t particularly love. Stuff with no serious meaning to it. Stuff I didn’t care about. Stuff that, if you had secretly tossed, I wouldn’t even realize went missing. Stuff I bought because it was trendy at the time, because my friend had it, because I had seen attractive influencers my age brag about it on Instagram, and it made me think that I could be her.

So, I did a bit of Marie Kondo-ing and produced a few large bags of clothes and trinkets and stuff for donation. Standing in front of all my stuff, it hit me that all of it used to be money, and all of that used to be time. I was standing in front of the metabolic waste of my existence, materialized. I was looking at the amount of my time, therefore my life, that had been turned into garbage. And the worst part is that I could’ve prevented it.

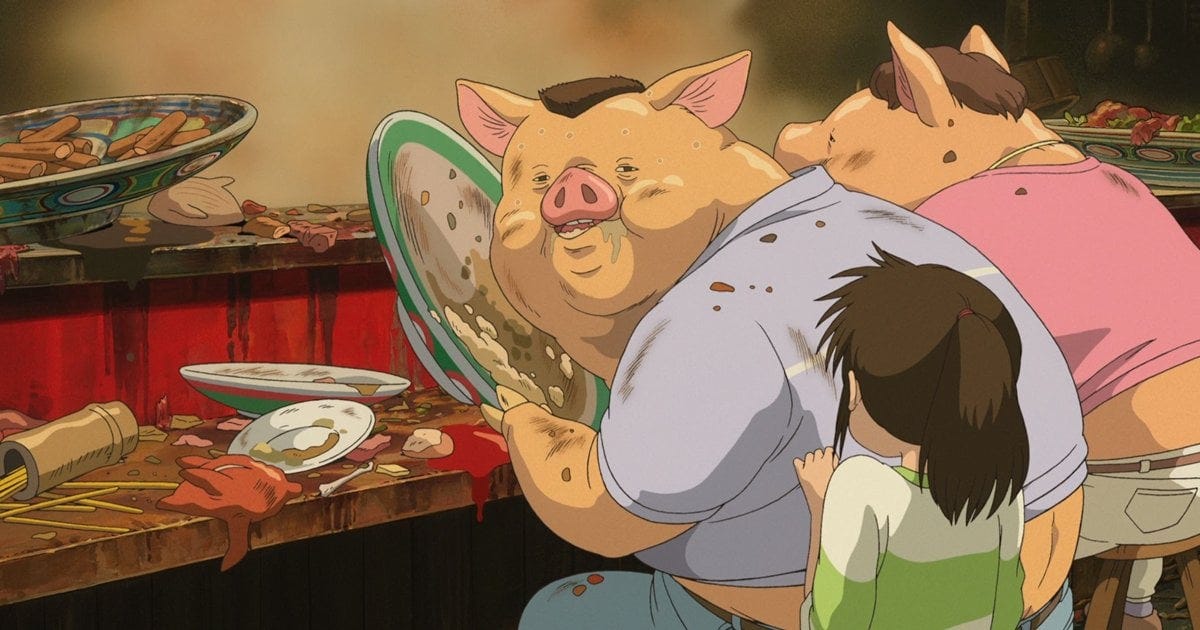

A movie scene that has stuck with me for years comes from Spirited Away, where Chihiro finds her parents turned into pigs. It’s comical to describe, but when you put yourself in her shoes, it’s terrifying: it’s every child’s nightmare to lose their parents to a force they can’t control. The panic she feels in that scene speaks to me deeply, the feeling of watching your loved ones do something that you know is wrong but being called “silly” when you try to stop them.

Materialism isn’t inherently evil; it can be gorgeous through the frames of abundance or art. Miranda Priestly’s “stuff” monologue from The Devil Wears Prada, for example, shows how material creates jobs, fuels culture, and shapes history. Miyazaki’s plates of food are dramatically overblown and colorful and delicious, but Chihiro’s parents don’t think about what they consume, only about how much. When she confronts them, her father shrugs: “It’s okay. I have my credit card and some cash.”

This is the mindset that will make you waste your life away into bags of garbage: the idea that shopping is a material issue, and overconsumption is a budgeting problem, rather than a spiritual problem. It’s easy to be Spirited Away, whisked into another world operated by desires that come from ads and friends and fleeting trends. Your appetite for novelty and your fear of missing out sucks the joy out of you—the more you eat, the hungrier you are. The more you spend, the more vapid you feel. You lack spirit, not another fashion identity. You don’t need another aesthetic, you need stronger values.

The title Spirited Away in Japanese is Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, and kamikakushi means “hidden by the gods,” a folk belief where people mysteriously vanish into another realm. This film is about magical abduction and losing your identity. Chihiro loses her name and becomes “Sen”: to be spirited away is like being stolen from yourself, forgetting who you are under the influence of forces like greed, fear, anger—and who’s to say that emotions aren’t magical? That desires aren’t demonic possessions of the mind (“demonic” meaning “godlike divisive superfactor” in Greek)? Who’s to say that feeling horny isn’t its own kind of spell? We literally use “mania” and “craze” to describe the way people desire something: Beatlemania, the craze with Labubus, matcha being ‘all the rage’.

Lust, for example, is the feeling of wanting something really badly. It doesn’t have to be a carnal desire but it’s about a possessive craving that ends in a feeling of collapse, an appetite that, once appeased, reveals its emptiness:

Lust is the deceiver. Lust wrenches our lives until nothing matters except the one we think we love, and under that deceptive spell we kill for them, give all for them, and then, when we have what we have wanted, we discover that it is all an illusion and nothing is there. Lust is a voyage to nowhere, to an empty land, but some men just love such voyages and never care about the destination.

—Bernard Cornwell

Shopping has this effect on me, the voyage is more satisfying than the destination. There is such thing as post-purchase clarity: the moment when you buy something trendy and you suddenly sober up to how much you don’t care about it (let alone like it); you just want to be seen having it.

Who is No-Face?

Spirited Away is most known for the character with the least lines: a masked ghost who can conjure gold. He has no backstory, we only know that he is banned from entering the bathhouse. Chihiro, out of kindness, lets him in. No-Face is refused service at first, but the staff quickly compromise their values upon seeing his gold. They serenade him, “Welcome the rich man. He’s hard for you to miss. His butt keeps getting bigger, so there’s plenty to kiss!” while they fight for the gold nuggets that plop out of his fat hands. Then, he devours the workers in despair when he realizes their kindness is bought, and only Chihiro is genuine.

The painful part of loneliness is the realization that most people are ass-kissers and friendship is rare. Likewise, people feel the most alienated when they suddenly sober up to the fact that most of their desires are herd-driven, that most of them are no where close to the truth, if they even have a clear enough sense of what that is that matters to them. It’s like waking up from a trance state and realizing, What have I done to myself? I certainly felt this way standing in front of my garbage bags. Loneliness, alienation, addictions and self-defeating loops—these are not material problems, but ‘desire’ problems.

I’m finally coming to understand what Girard meant by,

“All desire is a desire for being.”

We think we want things, but every desire points to a way of life, a kind of person we long to become. Objects seduce us not with their utility but with their promise of transcendence—status, attention, belonging. That’s why No-Face has no face: he is desire itself, the appetite to become, the emptiness that consumes while wishing it were someone else.

Money reveals this: In Roman mythology, the temple of Juno Moneta was both sanctuary and mint (it’s where we get the words “money” and “monetary”). To strike a coin was to sanctify it with divine authority, so it circulated as both economic and spiritual power. It still does: money organizes meaning. Fiat currency works because we collectively believe it means something—fiat literally “let it be” in Latin—its meaning assigned by our shared narrative. And because money is tethered to desire, it doesn’t just reflect value; it follows it. It’s the pull of eyes when a sports car glides down a street. It’s Bernard Arnault, CEO of LVMH, saying “when you create desire, profits are a consequence.” Shopping is not independent from the spiritual realm that strips away our names, and it’s a very literal form of kamikakushi.

When we feel the weight of our limits, we start reaching toward idols to imitate, goals to chase, places to explore, people to meet. What we’re really chasing is a sense of immortality or infinity, something that lives longer than we ever will. We want to be remembered long after we’ve left a conversation, the company, the world.

Desire is never about the object itself. If it were, once you acquired it, the desire would vanish. Yet, your wardrobe keeps getting stuffier while you still find yourself with nothing to wear. Desire is about what the object seems to promise us: a fuller, richer existence. This is why Marie Kondo’s “spark joy” test is great: it reframes consumption as discernment. It asks whether an object raises your spirit or weighs it down. Left unchecked, your possessions take away your freedom to be who you are. As Fight Club says, “The things you own end up owning you.”

Every now and then, I feel my value system collapsing under the seduction of Alo’s knitwear sets through their windows. Overall, none of this is about “how to spend less”, it’s about the freedom to just be… you.

You are not your job, you’re not how much money you have in the bank. You are not the car you drive. You’re not the contents of your wallet. You are not your fucking khakis.

—Chuck Palahniuk (Fight Club)

Stronger values make you spend more mindfully because they shift the axis of desire. When you know what you worship—what you actually stand for and who you want to become—everything gets tested against that vision. Values act like a sieve: they filter out the empty cravings that come from comparison and they let through only the things that genuinely serve your spirit. Without values, desires lead you astray by following ads and algorithms and the envy of friends—a state commonly known as “being distracted”.

The scariest part of Chihiro watching her parents turn into pigs is that they could’ve simply walked away. The unattended food stalls feel like a test of whether one can resist charming distractions. Like the family in Spirited Away, you’re rarely forced to follow one desire over another (until you choose wrongly, and only later realize what you’ve done, if you realize it at all). But if you aim at your highest value—placing no other gods above it, coveting nothing of your neighbor’s—you free yourself from the distractions that split your soul and can refocus your being on becoming who you want to be.

~

P.S. if you enjoyed this, I recommend “Transcending the Rat Race” or “Stop Looking at Each Other” next.

Brilliant, as always, Sherry! I wrote about this here in my Dirge for Detritus:

"All that stuff used to be money.

All that money used to be time.

All that time used to be opportunity.

All that opportunity used to be energy.

All that energy used to be potential.

All that potential used to be dreams.

All those dreams used to be yours."

Now, they’ve come down from the clouds and turned into clutter."

https://www.whitenoise.email/p/a-dirge-for-detritus

This is why the movie "Barbie" struck a deep, subconscious chord with its audience. Toys like Barbie don't teach kids reasoning, or a skill; they get them addicted to the temporary dopamine hit of the Shiny New Object. So they'll grow up believing if they just own the right brand clothing, jewelry, handbags, shoes, car etc. they’ll be “happy.” Only to discover a life devoted to mindless acquisition leaves them hollow and empty. Barbie had “all the right stuff;” the house, car, outfits, accessories – EVERYTHING. But she had no relationships deeper than “Hi, Barbie!”, no bond with Ken, who’s supposed to be her boyfriend; the sand was fake, the waves, cardboard – her entire world and identity were as fake as the plastic she's made from. So in the movie, Barbieland came to symbolize the false promise of materialism – a world where having everything means nothing. In the end, Barbie realizes – and this is a metaphor – that to become a Real Person, to find what it means to be a Real Woman, she has to LEAVE Barbieland, to go out into the Real World to find a life of meaning. She was the most "desirable" Barbie of all – a toy whose body proportions no human woman could ever achieve, whose endless possessions almost no real woman could ever accumulate, because the goal line keeps moving – this year it’s THESE clothes and THOSE shoes and THAT handbag that are in fashion. Barbie made young children yearn to be what they could never be, but grow up buying, buying, buying in an attempt to achieve the unattainable. So a story about THE iconic toy that started children down this path, in which that very toy ultimately has to LEAVE that fake world to become "Real" was the ideal vehicle for this message. Barbie herself gave viewers "permission" to leave false, materialistic values behind. People who believe their significance is tied to their possessions hated the movie. But vast numbers of viewers found it to have a very freeing, liberating, encouraging message. Which just crawled out from beneath the woodwork, without beating anyone over the head. Its “point” was simply the organic result of the story; a deceptively-deep story of Self Discovery that registered just below the realm of conscious awareness. Which is why it struck such a powerful, subconscious chord with viewers.