Who are you forcing yourself to be?

Babygirl (2024) is about the desire for honest, unapologetic, babylike wanting. + recommendations

When we’re tired, we want to be a baby again—not literally, but we want to feel that unapologetic joy of wanting without permission, like a baby selfishly putting her hunger first, seeking a nipple, unbothered by who’s watching.

But desires get tempered by expectations and standards, and rightly so, or chaos would reign. But where do those forbidden desires go, the ones that don’t fit who we tell ourselves we’re supposed to be?

Babygirl isn’t about temptation, betrayal, or rebellion. It’s about desire in the purest sense—that infantile state of wanting, unburdened by duty.

Romy’s lifestyle is created through self-flagellating optimization, and what she really wants is to be free from that muzzle of image-obsession. It’s one thing to desire something forbidden and accept that you can’t act on it; it’s another to bullshit yourself about not having those desires at all, to waterboard yourself until you feel purified, to slap some duct tape on the crying, hungry mouth of your desperate appetite.

She wants the feeling of wanting, unblemished by the wagging finger of shame, guilt, and embarrassment. She wants something beyond a lifestyle, because underneath the high-powered career and cryotherapy, she’s tired of observing herself from third-person. She’s tired of being the director and actress of her own show—a puppet of a woman, marching forward to the beat of pragmatism. What Romy really wants is to feel ALIVE: she doesn’t want to perform, she wants to be. She wants to experience the experience, not observe it from ‘somewhere else’.

*

In contrast, her rebellious teenage daughter rejects the marionette strings. I feel like she’s who Romy wishes to be in secret, if she wasn’t so hellbent on pretense. That’s why the club makes her feel alive—anonymity allows her to be herself.

The loud music, darkness, and the crowdedness melt away her religion of being the perfect mom/wife/CEO/woman. Only when she’s sure that nobody cares, she lowers her mask.

*

I love the title: Babygirl. One word. Not “baby girl” as in an actual female infant, but Babygirl. It’s a designation—an adorable pet name. Babygirl is a walled paradise where she’s allowed to seek pleasure simply, a desire she doesn’t need to explain with logic or hide her face under a pillow to get a taste of. Desire so pure it’s kept monastic, sealed in a bubble, protected from the rest of the world in hotel suites and locked office bathrooms. Desire untouched by fear and shame.

When Romy cheats—when she is Babygirl—her third-person POV collapses into a first-person POV, and observation becomes real experience. She goes from watching to being, from performing to feeling. She drops the choreography and starts living. She indulges in that ancient feminine desire to be taken, a la Genesis 3:16:

…thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.

Or, Sylvia Plath’s

Every woman adores a Fascist, // The boot in the face, the brute // Brute heart of a brute like you.

Or, Lana del Rey’s

I need you to come here and save me… Keep me forever, tell me you own me. (song: Off to the Races)

As a culture, we lack the vocabulary to describe this dynamic without sounding tyrannical—nobody actually wants to be harassed, injured, exploited, or humiliated, so the idea of being “owned” (in the eros way) and the idea of being enslaved are murkily connected.

Babygirl softly captures the dominant-submissive dynamic that our culture has trouble articulating. It expresses the female desire to be “owned” by pointing to the longing embedded in it: the desire to be taken care of, protected, claimed—but not harmed. The infantilization in the word is about being cherished, not actually being a baby. Babygirl removes the idea of abuse or slavery from dominance, and it nurtures the idea of submission without it meaning literal, unsexy oppression.

Collapse or liberation?

People who think that the movie had some moral lesson on infidelity missed the point: it’s not about cheating being reconcilable or whatever, it’s about the way we neuter our desires because we’re scared of what it might make us do:

Babygirl is about the feelings we have about temptation, not temptation itself. We’re scared of losing total control if we give in, so we become dishonest about our desires instead of learning to control it. (Especially the high-achieving, intelligent, eager-to-please, conscientious type that guilt-trips themselves for breaking their own rules. Sounds like you? Read this). The movie is about the inner animal that doesn’t evolve, a wild thing that doesn’t care about rules. It’s about hunger in the purest form. It’s about a woman whose obsession with image finally breaks her. It’s psychosis that erupts in the form of an affair.

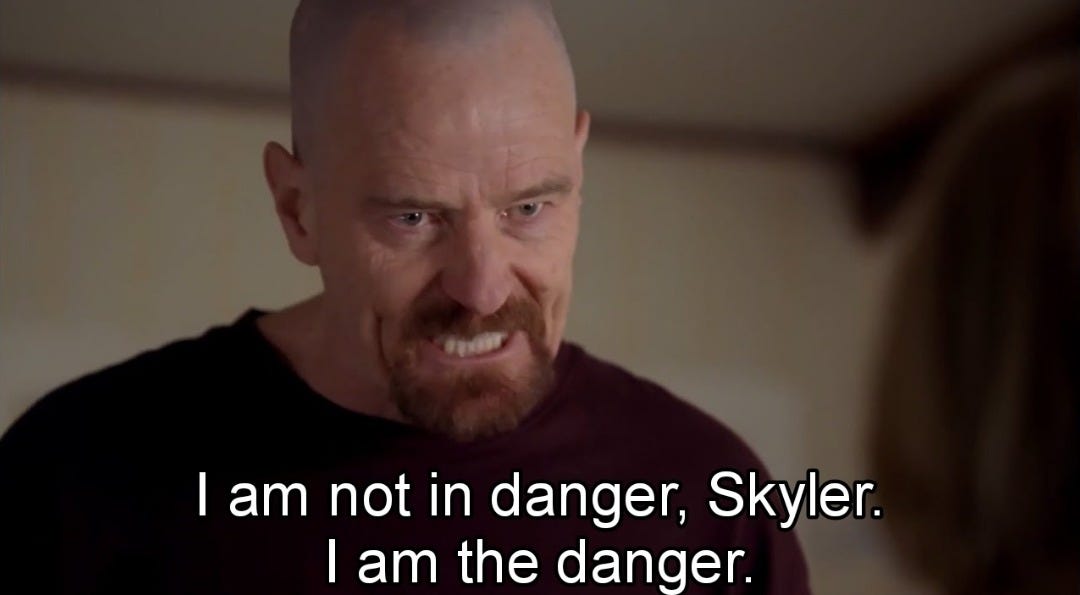

Romy reminds me of Walter White from Breaking Bad. If Babygirl is about a girlboss indulging in her fantasy of submission, Breaking Bad is about a “nice guy” living out his fantasy of dominance: Walter is belittled for having no aggression—he’s nagged by his wife, pushed around by his in-laws, pitied by his ex-cofounder who’s now a multibillionaire while he’s stuck teaching high school chemistry (to students who bully him)—he finally snaps and unleashes his vengeful hunger for power by becoming a meth kingpin. Both stories are about an appetite caused by chronic dissatisfaction, restrained until the glass cracks.

*

I think Babygirl challenges us to be honest with ourselves and examine the ways we are performing (or being pretentious) in our everyday lives.

Desire doesn’t like being compartmentalized, even though sometimes it has to be. The soul is oriented toward purity—it seeks Eden. It seeks play in that prelapsian way, the kind of fun that feels straightforward, innocent, and simple. This might sound paradoxical given the subject matter of the movie, but what I mean is that the soul wants wanting that’s uncomplicated by the world (everything comes back to Catholicism, doesn’t it?). Unfortunately, for Romy, infidelity became the way she would briefly face the desire she was ashamed of.

So, who are you forcing yourself to be? And who are you allowing yourself to be? Who would you be if you mastered your desires instead of fearing them (or, at the very least, befriended them)? Who would you be if you didn’t let your persona live your life for you? When are you watching, and when are you being? What are you repressing and why?

RELATED RECS:

“What happens when women hide their desires?” by Camille Sojit Pejcha

“Great Art is about being seen while remaining invisible” by Isabel

“standing on the shoulders of complex female characters” by rayne fisher-quann

“Christian Ecstasy”: the parallel between erotic and agape love

“Civilization and its Discontents” by Freud. It’s about the ways we must repress ourselves so we can function as a society, and the deviant behaviors that happen as a byproduct of it (i.e., weird kinks, addictions, antisocial levels of sadism, etc.). The original German title, translated directly, means “the sickness in our culture.”

Until next time,

I'm so glad that you mentioned Civilization and its Discontents. This quote from it immediately came to mind: “Most people do not really want freedom, because freedom involves responsibility, and most people are frightened of responsibility.”

the comparison to breaking bad is A+