Show me! Show me more!

Artists, writers, and perverts, perverts, perverts.

To a truly curious mind that wants to get to the bottom of things, everything looks like a door left slightly ajar, something waiting to be explored:

The forbidden is alluring. The wives and concubines of a noble man were not allowed to be visited or even looked at by other men, and so the word “harem” comes from “haram”, the label of the sacred and forbidden.

Art lets us materialize this curiosity. It welcomes us as voyeurs:

*speaking of bathing, join the waitlist for a live reading next week!

Art as new eyes:

When asked about what inspired the creation of Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov said: “A caged baboon, when given a charcoal, the first thing the poor animal sketched was the bars of its own cage. And that’s what my baboon, Humbert Humbert, does [in the book], he’s drawing and shading and erasing and redrawing the bars of his cage… this cage [is his] obsessive and rather frightening love for this girl… It is the pattern of his passion.”

Nabokov flips the mind of a sophisticated predator inside-out, not to glorify it, but to expose the layers of sick, twisted obsession. By giving the taboo a voice, Nabokov doesn’t endorse it—he lays it bare, showing us evil that wears status and smiles, a wealthy wolf in sheep’s clothing. His message for us? There are Jeffrey Epsteins hiding in plain sight.

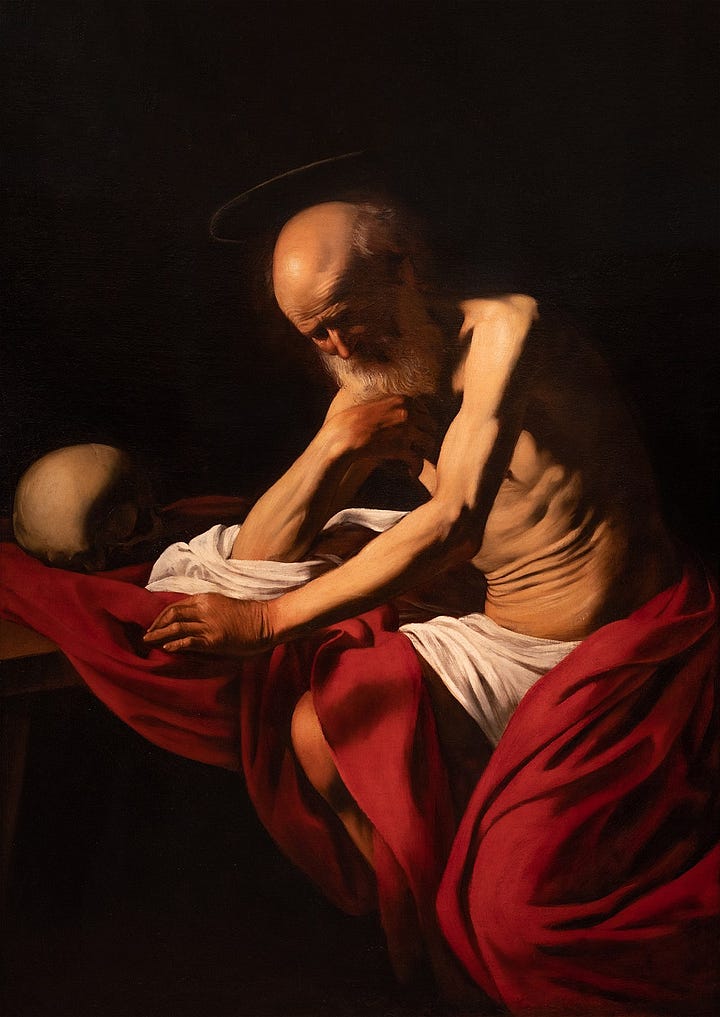

Artists find ways to reinterpret what’s been seen a million times, making us notice new details. If Nabokov exposed pedophiles, Caravaggio exposed saints: his paintings were infused with grit, showing virtue with dirty feet and wrinkly skin, as if to say, don’t expect saints to appear looking perfect—expect them to appear human, just like you.

Art as a confined space for dangerous ideas:

Art allows for a kind of experimentation with taboos that isn’t possible in real life. It’s a rehearsal space for alien possibilities, letting us entertain dangerous ideas without letting them kill us. It’s why Shakespeare could explore regicide in Macbeth or incest in Hamlet—on the stage, these taboos are transformed into something reflective.

Seneca (the Stoic) wrote Phaedra, a play about the Queen of Athens who falls in love with her stepson and hangs herself when he rejects her. Sophocles wrote the famous Oedipus Rex. Ancient Roman poet Catullus wrote about “bottoming Aurelius” among other lyrics that would make a rapper blush.

Freud said that incest is our most primal taboo because the people who first teach us love—our family—are the ones we are most forbidden to sleep with. This is what Nabokov poked at in Ada, or Ardor. It’s about the passionate, lifelong romance between a brother and a sister who were raised as cousins (because they were the product of an affair between in-laws).

Ada is whimsical, hypnotically Dionysiac, and some say it’s Nabokov’s most erotic work. What makes this book entertaining is the same reason why “Siblings or Dating” has over 1 million followers on Instagram: it lets people explore the boundaries of attraction through a playful lens, turning what could be seriously disgusting into something lighthearted. It lets us quietly unclench our fascination with the uncanny while keeping us at a comfortable distance from the haram. Turns out, we’re not that different from the audiences of Shakespeare, Sophocles, Seneca, and Catullus.

Lastly,

Art as fun:

Aesthetics can happen without moral lessons.

Premiered in 1913, the ballet Jeux (“Games”) was commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev to reflect modern life with playfulness, moving away from traditional mythological or historical themes.

Jeux is about a young man and two young women playing tennis and chasing a lost ball in a twilight garden, a game that gets touchier as the sun sets. It’s fun, it’s flirty, it’s ambiguous, it’s youthful—it blurs the lines between play and seduction.

Swan Lake was about how love defeats evil. Giselle was about mercy. Romeo and Juliet was about the destructiveness of prejudice. What’s Jeux about? A threesome at the country club? Well, it doesn’t matter.

The conclusion isn’t that there’s a correlation between creativity and deviancy, it’s that the willingness to twist convention is often the driver of art. Without people who have a taste for weird, avant-garde things (literally, “to be ahead of the troop”), culture dies. The mainstream, by definition, self-cannibalizes: it normalizes what it touches until there is no more novelty to it.

When I talk about perverts, I’m not talking about garden variety creeps. I mean it in the purest sense of the word—pervertere, Latin for “to turn around.” It’s about taking a look at the backside of things, where no one is looking (I HAVE AN ENTIRE POST ON THIS), then showing the world what no one has seen.

Ending quote:

A writer, I think, is someone who pays attention to the world. That means trying to understand, take in, connect with, what wickedness human beings are capable of; and not be corrupted—made cynical, superficial—by this understanding.

—Susan Sontag

~

Fin,

This is a brilliant, provocative exploration of art’s relationship with the forbidden, and it deserves a response that does more than nod in agreement.

Art has always been the safest place to wrestle with danger, not because it tames the dangerous, but because it forces us to stare at it without blinking. This is why the Church commissioned Michelangelo even as it feared the rawness of flesh, why Lolita remains uncomfortably relevant decades after Epstein’s private jet made the news, and why Shakespeare could have his actors commit crimes on stage without losing his royal patronage.

You mention “Lolita”, but let’s look at “American Psycho”, another work that gets misunderstood by those who can’t stomach its grotesque mirror. The book wasn’t about glamorising violence but about how modernity packages it in designer suits and expensive cologne. Nabokov made us see Humbert Humbert’s cage, Ellis made us hear the hollow echo inside Patrick Bateman’s soul. Both expose the monstrous underbelly of sophistication — one in literature, the other in finance.

And your point about avant-garde artists as perverts in the purest sense is perfect. True artists don’t just defy taboos, they reinvent how we see them. Think of the Surrealists — Dali turning Freudian nightmares into dripping clocks, Buñuel slitting an eyeball in “Un Chien Andalou” so we can never watch films the same way again. Or Picasso, who twisted the human body until it looked as fragmented as the world around him. They weren’t just weird for the sake of weirdness, they were offering new angles, forcing us to witness the hidden geometry of thought.

As for art without moral lessons, I’d go even further: sometimes, art is most powerful because it refuses to moralise. Duchamp’s urinal, Warhol’s soup cans, Cage’s 4’33” — all of them absurd, irreverent, challenging not just what we look at but how we look. “Jeux”, as you point out, doesn’t need to be about love or fate or mercy; sometimes, the point of art is simply to remind us that life is playful, and meaning is what we make of it.

In the end, the line between heresy and genius is always thin. Today’s blasphemy is tomorrow’s masterpiece. The pervert, the contrarian, the provocateur — they are the ones keeping culture alive, precisely because they refuse to let it harden into dogma. Keep looking where no one else is looking. That’s where the future is hiding.

It’s refreshing and inspiring to witness and benefit from your courageous provocations. Thank you.